Series Contents:

The science of measuring light, photometry, specifically applies to light in a space. Photometrics gauges how humans perceive light — its coverage area, i.e., where light cuts off, where its lost and the intensity of light in relation to distance from the light source.

In practical terms, photometrics shows whether a lighting plan meets the quantitative lighting requirements for a project. Proper use of photometry can improve the user experience in a space and can lead to more energy-efficient lighting, helping the property owner grasp where, how and what’s necessary to light a space optimally.

In short, photometrics is the study of the measurement of light. To understand essential photometrics principles, consider its seven main means of measurement.

Lumens: Lumen output, also known as brightness or light output, is a measure of the total quantity of visible light emitted by a light source. The reference point is a standard 100-watt incandescent light bulb producing about 1,200 to 1,500 lumens. Use the lumen method, the most commonly used light output formula, to calculate the total light output needs for your space.

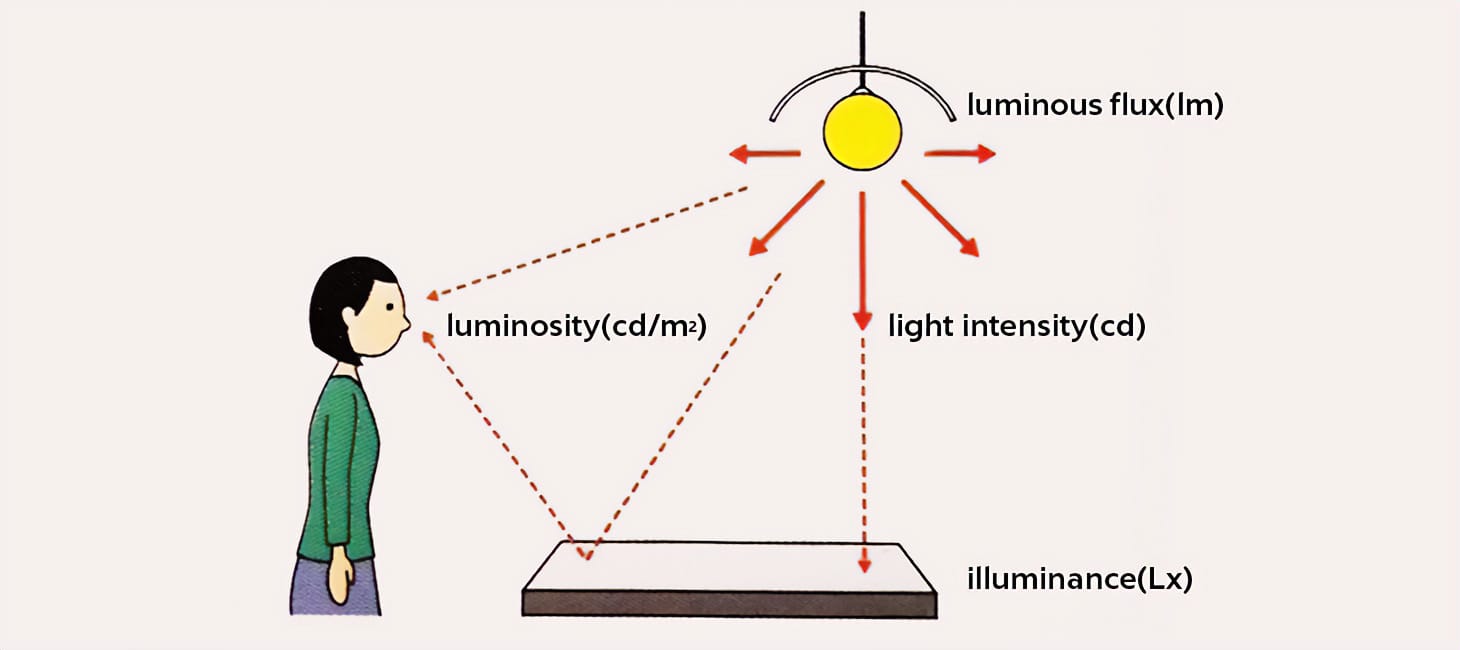

Candela: Luminous intensity, measured in candela, is the amount of light produced in a specific direction. Graphically, this data is gathered into polar-formatted charts that pinpoint light intensity at each angle away from a zero-degree lamp axis. The numeric information is also available in tabular form.

Lux: Lux, also known as illuminance, is the measurement of lumen output or luminous flux per unit area. In the study of photometrics, it is used as a measure of the intensity, as perceived by the human eye, of light that hits a surface. A flux of 1,000 lumens, concentrated into an area of 1 square meter, lights up that square meter with an illuminance of 1,000 lux. However, the same 1,000 lumens, spread out over 10 square meters, produces a dimmer illuminance of only 100 lux.[1]

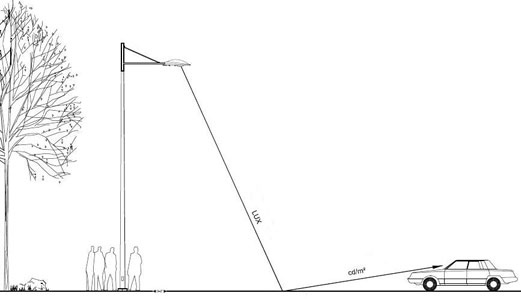

Foot Candles: Illuminance, measured in foot candles, measures the quantity of light on a surface. Three factors determining illuminance include intensity of the luminaire in the direction of the surface, distance from the luminaire to the surface and angle of incidence of the arriving light.

Candelas/meter2: Candelas/meter2 measures the quantity of light that leaves a surface. This is what the eye perceives. This means gauging luminance, which reveals more about design quality and comfort than illuminance alone.

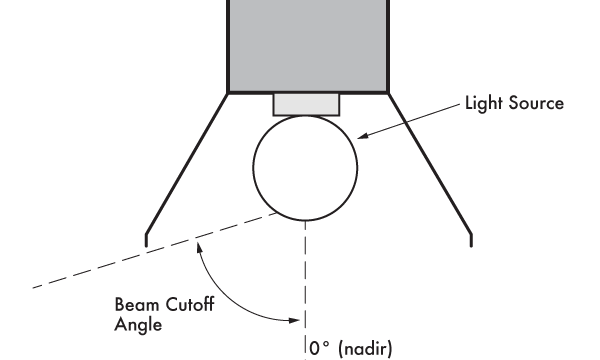

Cutoff: Cutoff refers to the angle between light’s vertical axis (the nadir) and the sight line, where the brightness of the source is no longer visible. The cutoff angle is the primary factor for a lighting designer to judge visual comfort. Deep cutoff optics provide low brightness, adding visual clarity.

Beam Aiming, Beam Spread and Cone of Light: A beam aiming diagram enables the architect or lighting designer to ascertain the best distance from which to locate and center the light source while the beam spread measures the width of a light beam from a light source. The number of a beam spread refers to the angle at which a given area is lighted. In other words, beam spread helps determine the coverage area for illuminating an object or task and knowing the beam spread helps the designer or architect gauge the right volume and type of light bulbs. A calculation of initial foot candle levels according to certain beam diameters is known as a cone of light.