Despite the notion that gentrification tends to disrupt communities and destroy neighborhoods, gentrification is an opportunity to listen, learn and build community cohesion, according to the late Jane Jacobs and Liz Ogbu.

Can gentrification be a force for good?

Let’s start with two key reasons gentrification occurs: a population increase and a housing shortage. Shrinking housing supplies and rising real estate prices make once affordable neighborhoods less affordable. When that happens, more people become willing to either accept a longer commute to work or live slightly farther from their favorite part of town. In exchange for less expensive and larger houses, they begin buying property on the periphery of the city, “gentrifying” lower middle class enclaves. As property values increase in the gentrifying neighborhood, new businesses start to meet the needs and wants of a more affluent demographic. Meanwhile, the poorer people who used to live in the “old” neighborhood find themselves getting pushed farther out or, in worst cases, into the streets.

Rising land values and increasing income disparities may make it seem like, for many neighborhoods, the prospect of gentrification is inevitable. But is there a way to gentrify so that communities and the people who live in them — no matter where they are in the financial spectrum — come out ahead?

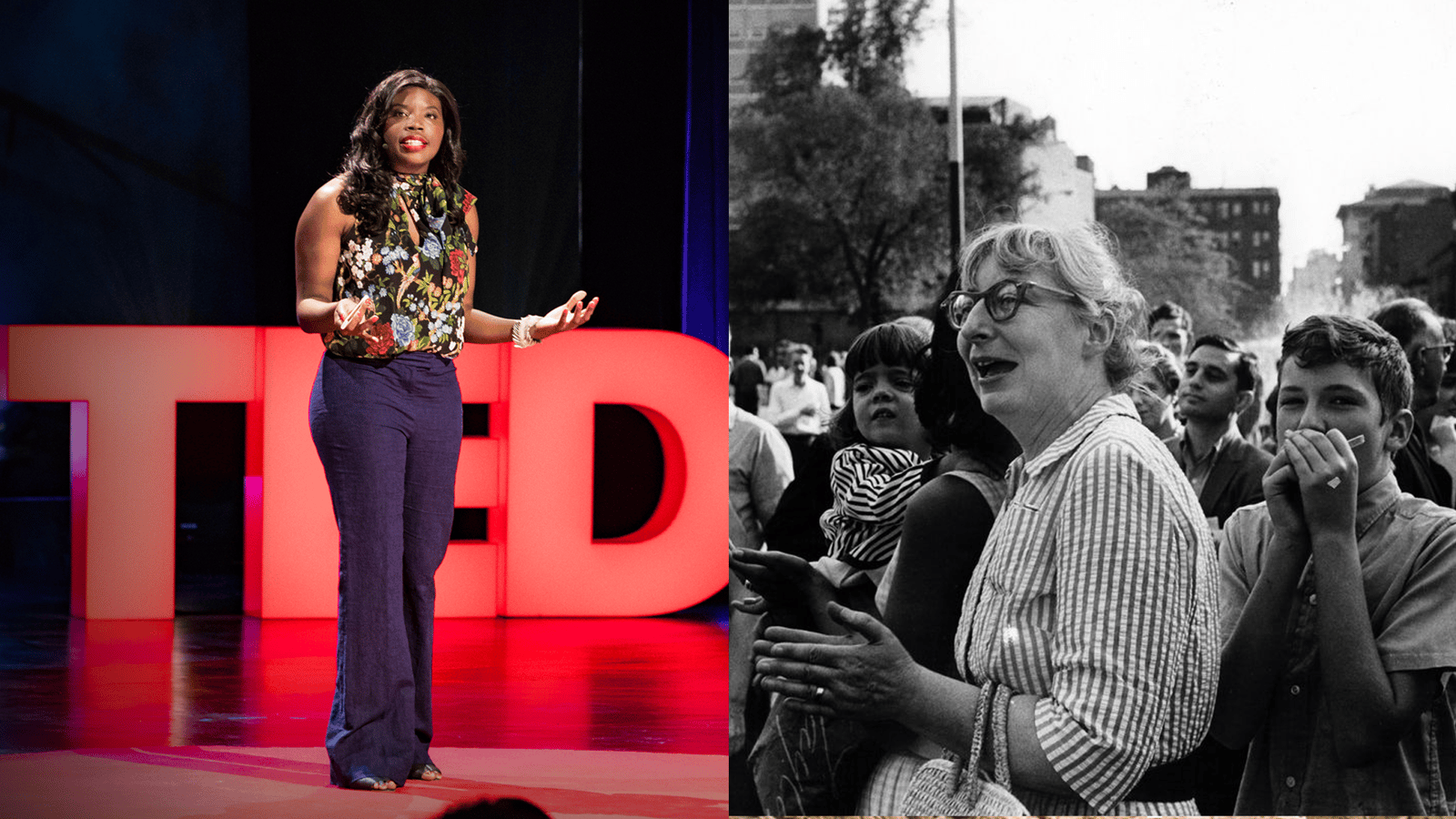

Both the late Brooklyn anthropologist, sociologist and urban planner Jane Jacobs and San Francisco architect and activist Liz Ogbu answer Yes.

In her 1962 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs defended the need to protect the unique character of a neighborhood, including its diversity of houses, buildings, public spaces and diversity of residents — as part of its identity. Jacobs also believed that on a micro level, interactions on city sidewalks reflect and shape the macro — the country as a whole. “Trust within a city is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts,” Jacobs wrote, adding that “sidewalk contact and safety, together, can thwart segregation and racial discrimination.”

However, Jacobs did not oppose progress. Her point was to recognize the value that exists within a city and then strive to add to it and strengthen it, as opposed to the notion of urban renewal, which suggests wiping out the old and building anew. In fact, to Jacobs, writing in her Dark Age Ahead, gentrification benefits neighborhoods, “but so much less than it could have if the displaced people had been recognized as community assets worth retaining.”

Jane Jacobs on Urban Planning

Jacobs blamed urban planners. According to them, a shortage of housing simply signals the need to build more housing and to build housing taller. She considered such rapid re-development and urban renewal potentially dangerous and destructive. Urban planners are lost in strategic planning, master planning, zoning and landscaping, she argued. These concepts are important, but not at the expense of the role of space, particularly public space, and what fills the space between public and buildable space.

To Jacobs, cities thrive on diversity, specifically diversity of people and diversity of locations, such as parks, buildings, bars and restaurants. Perhaps how we develop and address the microcosm of a city economy reflects on the macrocosm, i.e., the country, she suggested. In her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs lashed out against the Utopian vision of perfect, static designs she called “the dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and be served.”

The Alternative? Gentrify with Discretion

In her recent TED talk, architect and activist Liz Ogbu suggests that cultural erasure and economic displacement don’t have to be inevitable consequences of progress or gentrification. She argues that too often we see lower class lifestyles bulldozed to make way for higher class lifestyles. According to Ogbu, “poor people don’t hate gentrification, they just hate that they don’t get to hang around to watch its benefits.”

Ogbu goes on to say that, “if you’ve ever been displaced, then you know the agony of losing a place that held your story. Imagine walking home from your favorite local spot and opening a letter from your landlord that says your rent has been doubled.”

Similar to Jacobs’ counsel to listen to local voices to understand what would help rejuvenate or build on a local place without replacing the fabric of the neighborhood, Ogbu suggests that “we cannot create neighborhoods for everyone unless we’re willing to first listen to everyone.” Ogbu goes on to say that she’s never visited a gentrified neighborhood where pain didn’t exist and the potential for healing is absent. And the healing isn’t just for the poor. She asserts that “for those of us with privilege, we have to have a reckoning with guilt, discomfort and complicity.”

The rich or middle class might hear “gentrification” and think about how they’ll get in on a good real estate deal and make an investment that will pay off in the foreseeable future. Even so, the concept of gentrification probably may makes them feel uneasy, even guilty, about those displaced. Yes, they want a cool or new or hip place to live, but even so, they don’t want to kick other people out of their homes. She goes on to say that we can find value in the old stories and the new ones too as long as we “make a commitment to build people’s capacity to stay, to stay in their homes, to stay in the communities, to stay where they feel whole.”

There are great examples of cities gentrifying all over the country.

Kalima Rose’s in-depth analysis Combatting Gentrification Through Equitable Development lists four core anti-displacement strategies with a list of tools and examples of cities such as Brooklyn and East Palo Alto that help establish equitable development for current residents. The four core strategies are: stabilize existing renters, control land for community development, build income and assets creation, and develop financing strategies. Rose goes on to provide a list of tools for each of the core strategies, which include: community land trusts (CLTs), limited-equity housing cooperatives, housing trust funds, and inclusionary zoning and below market rate (BMR) ordinances.

According to The Daily Texan, a new Anti-Displacement Task Force was put together in Austin in January of this year collaborating with university professors to tackle gentrification. Austinites are discussing government programs based on ideas Rose mentions above, including a low-income housing trust fund, rent and eviction controls, and a “right to stay” program. Both Ogbu and Jacobs would probably be pleased of the task force’s primary goal, which is for its members and the residents of Austin to gather, speak and listen. “Coming out to hear people speak, we are hearing what [Austinites are] going through, what could be done or should have been done a long time ago,” said task force member Yvette Crawford-Lee.

San Diego-based writer Parisa Ijadi-Maghsoodi said she believes rent control can aid in alleviating California’s housing crisis. In her article “Demystifying Rent Control“, she argues that “rent control can help solve California’s housing affordability and homelessness crisis by decreasing displacement and protecting the rights and dignity of working families, the elderly, and long-term tenants.” Since 2016, rent control ordinances have been successfully enacted in Richmond and Mountain View, and rent control campaigns are underway in Long Beach, Glendale, Santa Cruz, Pasadena, San Diego, Inglewood, Sacramento, Santa Rosa, and Concord so long as the ordinances are “reasonably calculated to eliminate excessive rents and at the same time provide landlords with a just and reasonable return on their property.”

On March 18, 2018, community members, leaders and organizers gathered in New York for the official launch of the 7-Train Coalition. The coalition “formed to fight gentrification and housing privatization and end displacement in neighborhoods along the 7 line (Long Island City, Astoria, Sunnyside, Woodside, Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, Corona and downtown Flushing). The coalition is made up of Queens-based grassroots organizations, including the Queens Anti-Gentrification Project, Anakbayan New York, Migrante New York and the Coalition to Defend Corona.

“The idea is to build a bottom-up vision and plan for the community, to come up with our own — not big businesses’ or nonprofits’ — ideas of how to improve the neighborhood,” said Mike Legaspi, one of the event organizers. “While it’s true there are a lot of things to fix, we as a coalition believe that this development needs to be community-controlled, not corporate-controlled.”[1]

Obstacles can present themselves in the form of municipal NIMBYism (Not In My Backyard). Government officials may equate gentrification with higher tax revenue present another barrier. For example, California legislators are considering enacting statewide rent control and repealing Costa-Hawkins, a law that currently prevents rent control from applying to properties built after 1995. In efforts to alleviate the housing and homelessness crisis, rent control advocates claim that simply changing the 1995 to 2005 will dramatically reduce homelessness and improve housing.

In adding one short sentence to the state law can save 50,000 from homelessness, the Sacramento Bee’s Daniel Bramzon recently reported that, “in 2017, with virtually no fanfare, the appellate division of the Los Angeles County Superior Court wiped out a critical piece of West Hollywood’s rent stabilization ordinance. The provision allowed tenants to get reimbursed for attorney fees when victorious in standing up for their rights during eviction proceedings. Because of this provision, tenants in West Hollywood were more likely to have a lawyer with them and, consequently, were some of the least likely tenants in California to be evicted and become homeless.”

Without this provision, tenants in rent-controlled buildings are not as likely to appeal an eviction with the help of an attorney for fear of losing and being responsible to pay their attorney fees.

In other words, rent control advocates argue, without this provision and similar legislation designed to protect the low-income residents of these neighborhoods, gentrification is likely to continue, pushing out long-time residents and undermining the community as a whole.

Alcon Lighting creative director and co-founder David Hakimi works to improve lighting through research, development and education. David strives for efficiency in lighting, affording architects, lighting designers and engineers the ability to maximize LED lighting design and application. David is a graduate of the University of California, Los Angeles, where he received a Bachelors in history. David also studied lighting design at IES in Los Angeles. He traces his and Alcon Lighting’s commitment to innovation, accountability, quality and value to lessons learned from his father, Mike Hakimi, a lighting craftsman, salesman and consultant in Southern California for more than four decades. Today’s lighting for commercial use requires a deep, complete understanding of smart lighting systems and controls. David takes pride in his lighting, energy controls and design knowledge. He is driven by the desire to share his insights into lighting specification and application. This quest to share his knowledge was the impetus for David to create Insights, Alcon Lighting’s blog and resource center for helping the reader understand lighting and its application to space.